Using Elixir and Elm for Conway's Game of Life

Conway’s Game of Life using Elixir and Elm

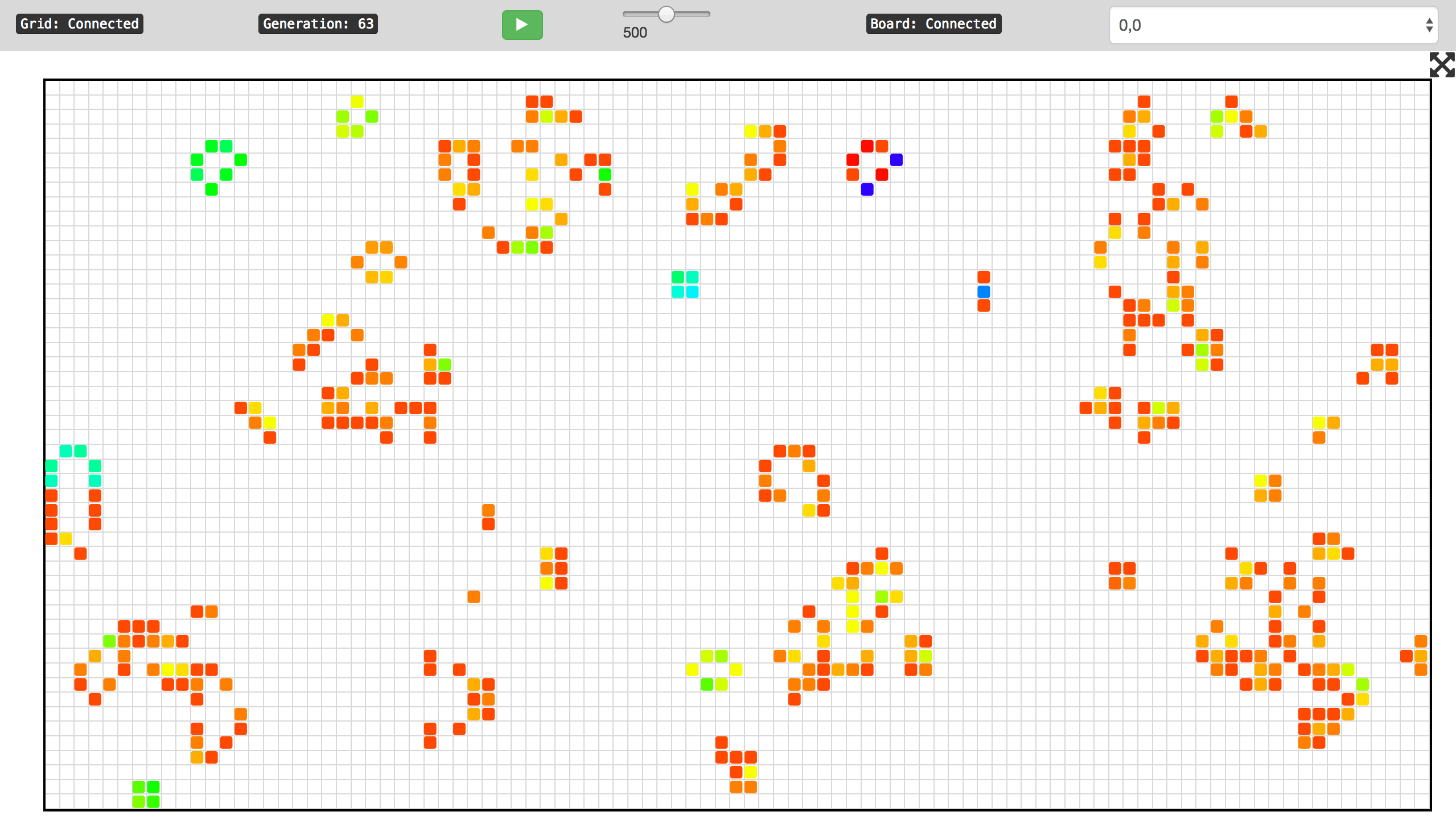

Myself and some colleagues recently used Conway’s Game of Life as a way to explore using Elixir, Phoenix and Elm. Here I will discuss some of the design choices we took and the outcome.

Why Game of Life?

The rules of Game of Life are quite simple. It consists of a grid of cells, where each cell can either be alive or dead. Whether a cell survives, dies or is generated in the next generation of the game depends only on its immediate eight surrounding cells. However, scaling it to run concurrently and producing a nice web based visualisation are non-trivial problems.

The solution can easily be split into three distinct parts, thus allowing three teams to work on each part almost independently once the interfaces have been agreed, with each part exploring different aspects of Elixir and/or Elm.

The three parts are:

Cell Calculation Algorithm

This, at its simplest, is a function that given a grid of cells, each of which has an alive/dead state, can return the grid of cells for the next generation of the simulation. Here the challenge lies in developing this using a functional programming language and designing an efficient way of representing the cells and calculating the next generation.

Parallelising and co-ordinating the problem

The most obvious way to scale the simulation, and the approach that we took, is to split the grid of cells into multiple rectangular ‘boards’ that represent a subset of cells. As a cell is influenced by its immediate surrounding eight cells, it is necessary for a board to transfer the state of the cells on its border to its neighbouring eight boards. That way the neighbouring boards can correctly calculate the state of the next generation of cells on their borders. Keeping track of all the boards, their relative positions to each other and the transmission of border cells between them concurrently is a problem ideally suited to the libraries offered in OTP such as Supervisor, GenServer and GenEvent.

Visualisation

The requirement here was to provide a nice web UI which would display the game simulation in real time showing the changing cells on the screen and allowing the user to stop, start and change the speed of the simulation and also to view which portion (or board) of the overall grid of cells they wish to view. The details of this is covered in this blog post:

Using Phoenix and Elm to Visualise Conway’s Game of Life

Cell calculation algorithm

Board Representation

We decided to represent the board using the following Elixir struct:

defstruct(

generation: 0, # generation number

origin: {0,0}, # this is the co-ordinates of the board's bottom left corner

size: {5,5}, # size of board {x,y}

alive_cells: %MapSet{}, # set of tuples of alive cells e.g. [{1,1}, {5,2}]. Bottom left is 0,0

foreign_alive_cells: %MapSet{}, # set of tuples of alive cells from neighbouring boards

)

Perhaps the most obvious representation of the cells is a two dimensional list or map with one entry per cell, and each entry being a boolean to indicate if the cell is alive or dead. However, the rules of Game of Life mean that the majority of cells are normally dead and hence a more efficient data structure, at least in terms of memory consumption is just storing which cells are currently alive. Thus we store a set of tuples where each tuple is the x and y co-ordinates of an alive cell. e.g.

%MapSet{ {1, 2}, {3, 4} }

We use a set (and not a list or map) to avoid having to deal manually with duplicates.

So as to distinguish between cells that we are responsible for calculating and those that come from the neighbouring boards and which we only use for the calculation of our own cells, we store them in a separate set, foreign_alive_cells. Getting all the cells can be simply done by a union of the two sets.

As we have multiple boards, we store the co-ordinates of the bottom left corner of the board also as a {x,y} tuple.

Next Generation Calculation

Calculating the next generation of cells (once we have the cells from the neighbouring boards in foreign_alive_cells) can then be done by:

- Merging

foreign_alive_cellsandalive_cellswithMapSet.union/2 - Calculating the set of cells that will survive to the next generation (those having 2 or 3 neighbours)

- Calculating the set of cells that will become alive in the next generation (those having 3 neighbours exactly)

- Merging the sets (2) and (3) together

Efficient algorithms for this are already a solved problem in the sphere of the mathematics of cellular automations such as Game of Life, and without doubt, our algorithm could be more efficient, but it is easy to understand and solves it in a purely functional way. It would be also nice if we could refactor this in the future to make the code more intuitive and ‘Elixirish’.

Storing the board state

Although we now have an algorithm for calculating the next board state from the previous generation, we need to persist the board to allow interactions via an API. For this we provided a thin GenServer API BoardServer on top of the board itself. The only state the the GenServer has is the board state itself:

defmodule GameOfLife.BoardServer do

alias GameOfLife.Board

use GenServer

defstruct board: %Board{}

...

end

API functions tell the board to generate its next state, return its current state, or update its foreign_alive_cells given a set of cells from a neighbouring board.

Parallelising and co-ordinating

The Grid

As mentioned previously, we wanted to parallelise the simulation and thus we split the overall grid of cells into multiple boards. In the grid we store a list of boards, with each board having an id which is a tuple for its bottom left co-ordinates. In order to communicate with each board (whose state is held in a separate BoardServer we need to store its PID in a map of board_ids to PIDs. e.g.

%{ {0,0} => #PID<0.61.0>, {50,50} => #PID<0.62.0> }

The Grid is also a GenServer providing API functions to add a board and get a list of boards.

The Ticker

As the Game of Life is turn based, we need something to co-ordinate the turn of each board so they all remained in sync and on the same generation. Our initial, and probably overly ambitious thought, was to allow the boards to control themselves just listening for a heartbeat message published to every board (every 500ms for example) from a central “ticker” to telling them to run the next generation. As well as providing regular heartbeats the ticker would also provide an API for stopping and starting the heartbeat and controlling its interval. This again would be a GenServer.

However, we realised that this would lead to race conditions and co-ordination problems if the interval was too short and one or more boards had not completed their next generation calculations before the next heartbeat arrived. So a simpler solution was just to provide a central run function which instructed boards to run their next generation as follows:

- Tell all boards to run their next turn

- Sleep for the interval configured in the ticker

- Repeat

Therefore although the ticker still provides an API for stopping and starting and controlling its interval, it no longer provides heartbeats, and can simply be used to query the period the currently configured interval.

Synchronising boards with their neighbours

To avoid a board having to be aware of its neighbours we instead decided to leverage the functionality of GenEvent. This provides a pubsub implementation allowing boards to publish their state and neighbouring boards to listen for updates. Creating a central event manager is very simple:

defmodule GameOfLife.EventManager do

use GenEvent

def start_link, do: {:ok, _pid} = GenEvent.start_link(name: __MODULE__)

end

Then once a board has completed calculating its next generation it can publish its new state to the EventManager:

GenEvent.notify(GameOfLife.EventManager, {:board_update, board})

Neighbouring boards can subscribe to the EventManager for board updates using: GenEvent.add_handler/3 and then act on the :board_update event:

def handle_event({:board_update, neighbour_board}, state) do

# Update the foreign cells in own board with

# neighbour_board cells that are on the corresponding edge

...

end

Source code

https://github.com/xing/game_of_life

Next steps

Next we build the visualisation which is covered here: